Lynch syndrome is the most common genetic condition that increases a person’s risk of developing bowel cancer.

It is caused by a change in a gene (the mismatch repair gene) that normally functions to protect a person from getting cancer.

Lynch syndrome can affect the best choice of treatment options for bowel cancer patients, and also has preventative health and screening implications for family members.

The bowel cancer risk in someone with Lynch syndrome is hundreds of times greater than the average.

But less than 5% of patients affected are aware of their risk because a simple test that could indicate the gene mistake is not being conducted.

“Anyone who is diagnosed with bowel cancer could be harbouring a genetic inheritance without knowing it,” Bowel Cancer Australia’s Community Engagement Manager Claire Annear said.

All bowel cancer patients, and particularly those diagnosed under the age of 50, should speak to their treating specialist about having their tumour screened for indicators of Lynch syndrome.

“The simple test helps ensure loved ones are aware of any possible risk, and able to then seek genetic counselling and testing if needed.” Ms Annear added.

Bowel Cancer Australia aims to empower patients with the knowledge and tools required to be advocates for their own health.

The 'Is Bowel Cancer in Your Genes?' infographic serves as a timely reminder to talk to loved ones about family history and genetic risk factors.

If you have any questions about bowel cancer and family history or genetic inheritance, contact Bowel Cancer Australia's team of friendly Bowel Care Nurses.

Every person inherits genes from both their parents and Lynch syndrome is caused by a fault in a gene that normally functions to protect a person from getting cancer (known as the 'mismatch repair' genes). The 'faulty' gene increases a carrier’s risk of developing bowel cancer and other types of related cancers e.g. some gynaecological cancers, digestive tract, urinary tract or brain cancer.

Where it runs in a family, Lynch syndrome can present itself as many different cancers across multiple family members.

If left untreated, the risk of developing bowel cancer in people with Lynch syndrome is 70-90 per cent.

Around 30 per cent of bowel cancer patients have a family history or genetic inheritance, both of which significantly increase a person’s risk of developing bowel cancer.

If a person is diagnosed with Lynch syndrome their parents, children, and siblings have a 50% chance of having the condition.

Identifying people that are carriers of Lynch syndrome allows for early and increased surveillance, the option of preventative surgery and the ability to determine increased cancer risk in the extended family.

People with Lynch syndrome are much more likely to develop bowel cancer, especially at a younger age.

Lynch syndrome can affect treatment options offered to those diagnosed with bowel cancer, so screening for the genetic fault should be performed at the time of diagnosis.

The latest clinical practice guidelines for the prevention, early detection and management of bowel cancer recommend universal testing of all bowel cancers for Lynch syndrome.

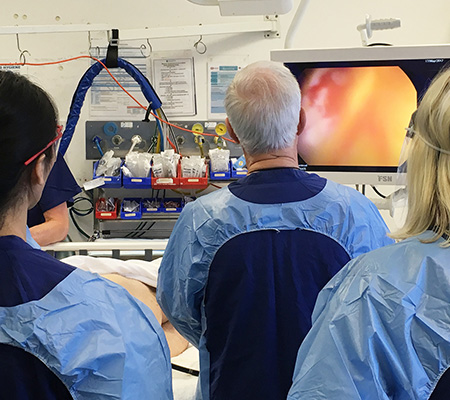

A simple screening test can be carried out on a patient's bowel cancer tumour tissue to identify if they are likely to have Lynch syndrome. If the screening test is positive the patient and their family can be referred for genetic testing.

You are your own best advocate.

If you have been diagnosed with bowel cancer, ensure your treating specialist performs the test that could help determine if your cancer may have been genetically inherited.

Bowel cancers in Lynch syndrome can develop much more quickly than those in the general population. But there is much that can be done to reduce the cancer risk in someone carrying the genetic mutation.

Identifying people that are carriers of Lynch syndrome allows for early and increased surveillance, the option of preventative surgery and the ability to determine increased cancer risk in the extended family.

Regular screening by colonoscopy has been shown to reduce both the incidence and mortality of bowel cancer in Lynch syndrome patients and affected family members.

Where Lynch syndrome is suspected in your family, your GP will refer you to a Family Cancer Clinic for support and ongoing management of the condition.

People with Lynch syndrome and those that may be at risk should immediately tell their GP about any possible bowel cancer symptoms.

Genetic testing looks for specific inherited changes (mutations) is a person’s chromosomes, genes, or proteins.

Some mutations can be harmful and may increase a person’s risk of developing cancer.

Genetic testing can confirm whether a condition, such as bowel cancer, is the result of an inherited syndrome. It can also help to determine whether family members without obvious illness have inherited the same mutations.

The best indicator of being at risk of bowel cancer is having a close relative who has bowel cancer, especially if they were diagnosed before 55 years of age.

Wherever possible, screening of tumour tissue from the bowel cancer patient should be completed first to help determine which gene is likely to be affected and if further genetic testing is appropriate.

These initial screening tests are looking for changes in the genetic information within the cancer cell and include Microsatellite instability (MSI) testing and Immunohistochemistry (IHC) testing.

If the family-specific gene mutation can be identified, other at-risk relatives can have a blood test to see if they have inherited the same mutation.

Genetic testing in Australia is arranged through Family Cancer Clinics, where professionals make sure that people receive all the support and help they may need to make decisions about testing.

A diagnosis of Lynch syndrome can have a major impact on the life of those affected and their family. As well as the need to keep up regular surveillance, there can be medical, emotional and financial repercussions, implications for future insurance, and difficult decisions regarding the possibility of passing the faulty gene on to future children.

The option to undertake genetic counselling is an important consideration, and one that is recommended for anyone considering genetic testing for Lynch syndrome.

The average age of onset for bowel cancer in people with Lynch syndrome is 40-50 years, as compared to 60-70 years amongst the general population.

Bowel Cancer Australia therefore recommends that all bowel cancer patients diagnosed under the age of 50 speak to their treating specialist about having their tumour screened for loss of expression of mismatch repair protein (an indicator of Lynch syndrome).

Routine screening not only helps to determine if a patient is at greater risk of cancer recurrence, it also helps to identify family members who may have the condition and be at risk of bowel cancer at a younger age too.

My name is Sarah I’m now 36 but I was diagnosed with bowel cancer back in May 2016 when I was 33! I am a mother of four children my youngest at the time was 2 and my eldest was 6.

They thought it was a gynaecology problem but once in there they realised that everything was healthy there they then called in the bowel surgeons who proceeded to tell me when I came out that I had a bowel infection and that I probably had diverticulitis and needed to change my diet.

Finally, at the 3-week mark he referred me to a surgeon. Who then suggested I have a colonoscopy. I’ve had irritable bowel syndrome for years and they have checked every type of bowel issue but never a colonoscopy.

That was the day - I came out of surgery and he gave me the news right away. My hubby came in and I was a mess. I thought that was it! However, I had four babies at home that needed me.

I then had all the scans under the sun and yes it had spread. To my bladder and uterus. So, I then had surgery to remove the tumour. I had 300mm of my bowel removed I lost my bladder, uterus, 1 ovary and appendix.

I then went through nine months of chemo and 12 rounds – I was smashed! It made me very ill. I lost 14kgs in a week. However, I made it through the other end. My husband was amazing I don’t know what I would have done without him.

I then found out it was genetic! I have Lynch syndrome. No history of bowel cancer. After having genetic testing done, I have helped a lot of family members find out they to also have Lynch syndrome.

Bowel Cancer Australia's Big Bowel is on the road.

An astounding 7.0 metres in length and 2.4 metres high, the walk through inflatable Big Bowel exhibition feature some of the pathologies that may be found inside the human bowel, including cancer.

This unique experience provides important health information, helping to encourage bowel cancer prevention and screening across the country. Visitors will view everything on a larger than life scale. The three-dimensional interior features healthy tissue, pre-cancerous polyps, advanced polyps, bowel cancer - a malignant tumour, diverticulitis and crohns disease.

A tour of the Big Bowel will benefit all visitors, showing them in a memorable way that bowel cancer is ‘treatable and beatable.’

The Big Bowel will be touring the country on a regular basis, and will appear at community centres, shopping malls, health expos, outdoor events and any place that can accommodate such an imposing presence.

{enquiry_healthycommunity}

Age | Family history | Hereditary risk | Genetic inheritence | Lynch syndrome | FAP | MAP | Crohn's disease | Ulcerative colitis

Anything that increases your chance of developing bowel cancer is called a cancer risk factor. Some risk factors can be avoided, but many cannot.

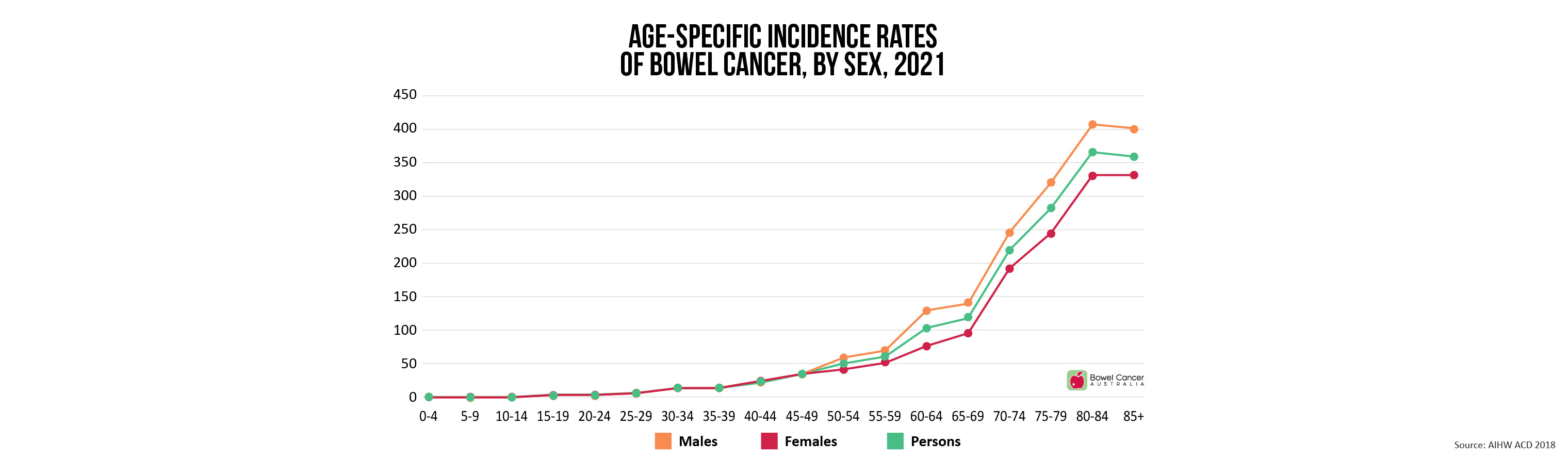

- Age - bowel cancer risk increases with age. Incidence begins to increase significantly between the ages of 40 and 50, and age-specific incidence rates increase in each succeeding decade thereafter (i.e. 50-60; 60-70; 70-80 etc). Although bowel cancer is less common among younger adults, rates are on the rise, with 1-in-10 bowel cancer cases now diagnosed in Australians under age 50.

- A family history of bowel cancer

- A personal history of cancer of the colon, rectum, ovary, endometrium, or breast

- A history of polyps in the colon

- A history of ulcerative colitis (ulcers in the lining of the large intestine) or Crohn's disease

- Hereditary conditions, such as Familial Adenomatous Polyposis (FAP) and Hereditary Non-Polyposis Colon Cancer (HNPCC; Lynch Syndrome).

About 70% of people who develop bowel cancer have no family history of the disease.

However, for around 30% of all bowel cancer cases diagnosed there is a family history, hereditary contribution or a combination of both.

Generally speaking, the more members of the family affected by bowel cancer, and the younger they were at diagnosis, the greater the chance of a family link.

Genetic mutations have been identified as the cause of inherited cancer risk in some bowel cancer–prone families; these mutations are estimated to account for only 5% to 10% of bowel cancer cases overall.

| What is my risk of hereditary bowel cancer?

The following may help you and your GP assess your personal level of risk.

High bowel cancer risk

Hereditary conditions

- Relatives diagnosed with Familial Adenomatous Polyposis (FAP)

- Relatives diagnosed with Lynch syndrome (HNPCC)

- Siblings of people with MYH-associated polyposis (an autosomal recessive condition)

- At least 3 first-degree or second-degree relatives diagnosed with bowel cancer, with at least one diagnosed before age 55 years; or

- At least 3 first-degree relatives diagnosed with bowel cancer at any age

Please note: a first-degree relative can be a parent, brother, sister or child.

A second-degree relative can be an aunt, uncle, grandparent, grandchild, niece, nephew, or half-brother or half-sister.

- One first-degree relative diagnosed with bowel cancer before age 55 years; or

- Two first-degree relatives diagnosed with bowel cancer at any age; or

- One first-degree relative and at least two second-degree relatives diagnosed with bowel cancer at any age

Personal health history

- Bowel cancer

- Special types of polyps, called adenomas

- Inflammatory bowel disease such as ulcerative colitis or Crohn's disease

Near average bowel cancer risk

- One first-degree relative diagnosed with bowel cancer at 55 years or older; or

- One first-degree relative and one second-degree relative diagnosed with bowel cancer at 55 years or older

Average bowel cancer risk

- Age 40 or over; and

- No symptoms to suggest bowel cancer; and

- No first-degree or second-degree relative diagnosed with bowel cancer.

The three most common inherited syndromes linked with bowel cancers are:

- Hereditary Non-Polyposis Colorectal Cancer (HNPCC) (also known as Lynch Syndrome)

- Familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP)

- MYH-Associated Polyposis (MAP)

In HNPCC, mutation carriers' lifetime risk for bowel or other syndrome cancers is 70-90%.

If a person has a HNPCC mutation, each of their children has a 50% chance of inheriting the mutation.

Lynch syndrome is caused by a change in a gene that normally functions to protect a person from getting cancer.

Each person inherits genes from both their parents and HNPCC is caused by a fault in one of the genes known as the 'mismatch repair' genes.

Someone who inherits HNPCC from their parents has a normal gene and a 'faulty' gene, which increases their risk of developing bowel cancer and other types of cancer.

HNPCC affects less than 5% of those who develop bowel cancer. Although rare, this risk relates to a clear family history of bowel or specific, related cancers e.g. some gynaecological cancers, digestive tract, urinary tract, brain or bowel cancer.

The typical age of diagnosis of this kind of Hereditary Non-Polyposis Colon Cancer (HNPCC or Lynch Syndrome) is usually between 40-50 years (compared to 60-70 years amongst the general population).

In families where there is a clear history of HNPCC, screening with colonoscopy every 1 to 2 years usually commences from age 25 or 5 years earlier than the youngest affected family member if they were diagnosed under 30, whichever comes first.

Where HNPCC is suspected, your GP will refer you to a Family Cancer Clinic for support and on-going management of the condition.

| Familial Adenomatous Polyposis (FAP)

An affected person has a 50% chance of passing the condition on to each of their children.

FAP is characterised by the presence of hundreds to thousands of adenomatous polyps in the large bowel of affected individuals, which often start in adolescence.

Cancerous polyps are very common in this condition, usually by age 40, without active management of the polyps and screening on a regular basis.

Diagnosis is usually made following colonoscopy to confirm the presence of polyposis. Testing for mutation of the APC gene currently detects 95% of mutations present.

In families where there is a clear history of FAP, annual screening via a flexible sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy usually commences from age of 10-15 or earlier if there are gastrointestinal symptoms.

Where FAP is suspected, your GP will refer you to a Family Cancer Clinic for support and on-going management of the condition, because it has been known to affect adolescents and teenagers.

The treatment for FAP is usually a planned operation to remove the affected part of the colon once polyposis has become established. This normally occurs in the late teens or early twenties.

These are very rare conditions and you will need the specialist help and support of an experienced colorectal team to help make the right decisions for the individual affected.

Although considered rare, people diagnosed with MYH-Associated Polyposis (MAP) have close to 100% risk of developing bowel cancer by the age of 65, if they are not monitored closely with colonoscopy.

MAP is characterised by the development of 10 to a few hundred polyps, which can develop into cancer.

A person has a 25% chance of being affected with MAP when both parents pass on the gene mutation.

MAP is a genetic condition caused by a mutation in the MYH gene, also known as the MUTYH gene.

In order for a person to have an increased risk of MAP, each parent must pass on a copy of the altered MUTYH gene.

A person who has only one copy of the gene mutation (from one parent) is called a carrier, and they are not at increased risk themselves. However they may pass the gene on to their children.

Most individuals with MAP will develop dozens, sometimes hundreds, of polyps, in their colon over their lifetime. It is rare that people with MAP will have no polyps present at all.

The risk of bowel cancer is increased if these polyps are not removed.

In families where there is a history of MAP, your GP will refer you to a Family Cancer Clinic for support and ongoing management of the condition.

Where MAP is suspected, individuals and families should undergo DNA testing, and test for MAP in those who do not have a mutation in the APC gene (APC gene associated with FAP/AFAP).

Do you know if anyone in your family has had bowel or any other kind of cancer? Talk to your family and make sure you all know your family history.

If you think that you have a strong family history of bowel cancer, you should make an appointment with your GP to talk about your concerns.

If your GP agrees with you, they will refer you to a Family Cancer Clinic.

A genetic specialist will go through your family history with you in great detail and ask you to provide accurate information about who has been affected, how old they were when they were diagnosed, and the site where their cancer developed.

You may also have to have blood tests as part of this investigation.

If the genetic specialist agrees you are at increased risk, you will be referred to a specialist to talk about what types of screening and/or surveillance they recommend, at what age you (and/or other family members) should commence screening and/or surveillance and how often.

Regular screening and/or surveillance will ensure that any signs of bowel cancer are detected and treated early.

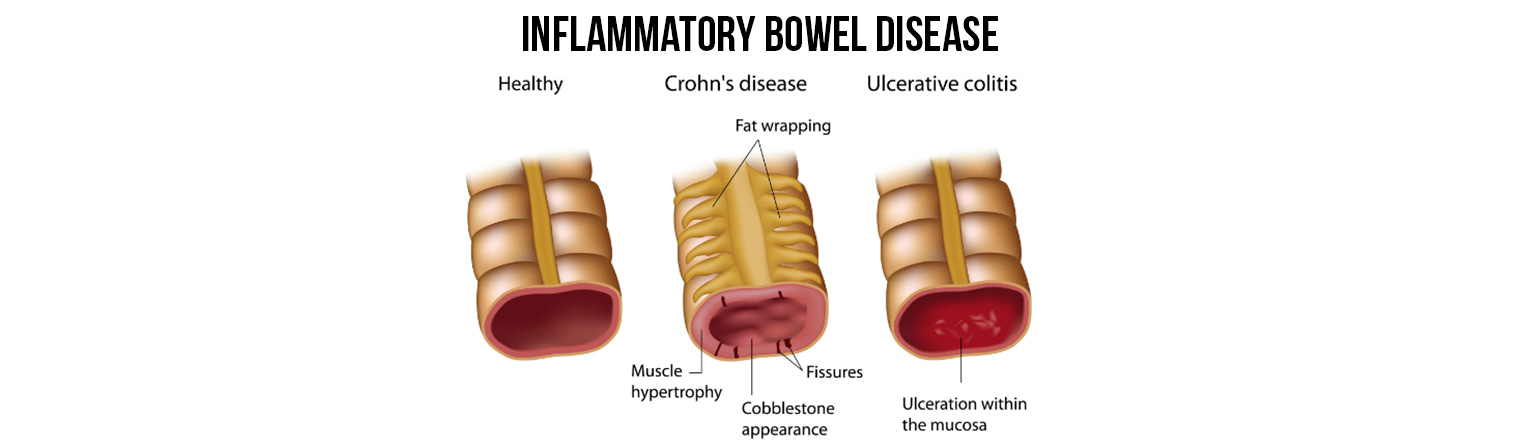

Inflammatory bowel disease is sometimes shortened to IBD. However, this is not the same as IBS, which is short for irritable bowel syndrome, and which is a very different condition.

Both these conditions can cause inflammation of the colon and rectum, with similar symptoms and treatments.

The main differences are that the inflammation of ulcerative colitis is usually found just in the inner lining of the gut, while in Crohn's disease the inflammation can spread through the whole wall of the gut.

In addition, ulcerative colitis only affects the colon and rectum, while Crohn's disease can affect any part of the gut.

Crohn's disease is a long-term condition that causes inflammation in the gut – the lining of the digestive system.

The inflammation usually occurs in the last section of the small intestine (ileum) or the large intestine (colon), but any part of the gut can be affected.

There may be a small patch of inflammation, or it may spread quite a way along the gut, or there may be several patches in different places.

In a few people, the mouth, gullet or stomach may be involved. More rarely, the condition also triggers inflammation outside the intestine leading to arthritis, eye inflammation or skin complaints.

In mild Crohn's disease, there are patches of inflammation with groups of small ulcers, similar to mouth ulcers.

In moderate or severe Crohn's disease, the ulcers are larger and deeper. The inflammation can thicken the intestine, blocking the passage of digested food.

In some cases, deep ulcers break through the intestine wall causing infection – an abscess – outside the bowel. This infection or abscess can spread to a nearby part of the body, often around the anus, and this is called a fistula.

Scar tissue can form as the inflammation heals, and in some cases this leads to a blockage in the intestine.

Who gets Crohn's disease?

Crohn's disease is a rare condition. It can develop at any age, but usually starts between the ages of 15 and 30, and between the ages of 60 and 80.

Crohn's disease affects slightly more women than men.

The condition runs in families, so those who have a family member with Crohn's disease are more likely to develop the condition too.

It is also more common in people who have had their appendix removed, for the first five years after the operation.

What causes Crohn's disease?

The exact cause is unknown. Most researchers think that it is caused by a combination of factors.

These include:

- Genetics

Inherited genes may increase the risk of developing Crohn's disease. - Immune system

One theory is that the immune system – the body's natural defence against infection and illness – is responsible for the inflammation in the digestive system. Crohn's disease disrupts the immune system, so that it no longer recognises the 'friendly bacteria' that help to digest food. - Previous infection

A previous infection, possibly in childhood, may trigger an abnormal response from the immune system. - Environmental factors

Crohn's disease is most common in countries with a modern western lifestyle, such as Australia, and least common in poorer parts of the world, such as Africa. This suggests that the environment has a part to play. - Smoking

Smokers are twice as likely to develop the disease compared with non-smokers. Smokers with Crohn's disease usually have more severe symptoms than non-smokers.

What are the symptoms?

The symptoms vary and depend on which part of the intestine is inflamed.

There may be long periods that last for weeks or months with very mild or no symptoms, known as remission.

This may be followed by periods when the symptoms are particularly troublesome, known as flare-ups.

Common symptoms include one or more of the following:

- recurring diarrhoea, often with a feeling of urgency to get to the toilet, and often with a feeling of wanting to go to the toilet but with nothing to pass

- abdominal pain and cramping, which is usually worse after eating

- extreme tiredness (fatigue)

- weight loss

Less common symptoms include:

- high temperature (fever) of 38°C or above

- feeling sick (nausea)

- being sick (vomiting)

- joint pain and swelling (arthritis)

- inflammation and irritation of the eyes

- skin rashes

- blood and mucus in poo, which may be the result of an ulcer bleeding

- anaemia, which may occur if there is a lot of blood loss

- mouth ulcers

If your GP suspects that the symptoms might point to Crohn's disease, a referral will be made to a specialist for diagnostic tests.

Is there a link between Crohn's disease and bowel cancer?

People with Crohn's disease have an increased risk of developing bowel cancer and should be monitored regularly.

The risk is related to the length of time that inflammation has been present, and the site and severity of the disease.

Several studies estimate the risk by following patients over a period of 10–40 years.

Some did not show an associated risk, but others predicted an increase that was twice that of the general population for developing bowel cancer.

If the disease is confined to the colon, this risk is estimated at around five times greater.

The risk of small intestinal cancer has been estimated at around six times that of the general population, but as this is an extremely rare cancer in the general population, the risk in Crohn's disease is still small.

While Crohn's disease and bowel cancer are two very different conditions, it is important to note that many of the symptoms are the same for both.

The signs and symptoms may vary according to the site and extent of the cancer, but mostly show a general worsening of the symptoms associated with Crohn's disease.

People with Crohn's disease are often unaware that they have bowel cancer, as the initial symptoms are similar to Crohn's disease, such as blood in your poo, diarrhoea and abdominal pain.

Because of this, you will probably be advised to have a colonoscopy every few years to check that no cancer has developed.

Ulcerative colitis is a long-term, chronic condition that usually occurs in the rectum (the part of the large bowel that lies just inside the anus) and lower part of the colon, but it may affect the entire colon (large intestine).

The colon becomes inflamed and, if this inflammation becomes severe, the lining of the colon is breached and ulcers may form.

The amount of inflammation in ulcerative colitis is very variable, and many people never develop ulcers, because their degree of inflammation is not that advanced.

In mild cases, the colon can look almost normal, but when the inflammation is widespread, the bowel can look very diseased and can contain ulcers.

Who gets ulcerative colitis?

The exact cause is unknown. Most researchers think that it is caused by a combination of factors. These include:

- Genetics

Inherited genes may increase the risk of developing ulcerative colitis.

- Immune system

Ulcerative colitis is called an autoimmune condition. This means the immune system – the body's natural defence against infection and illness – goes wrong in some way and attacks healthy tissue. One theory is that the immune system mistakes the harmless bacteria – the 'friendly bacteria' inside the colon that help to digest food – as a threat and attacks the tissues of the colon, causing it to become inflamed. - Environmental factors

Ulcerative colitis is most common in countries with a modern western lifestyle, such as Australia. This suggests that the environment has a part to play, and various factors have been suggested. These include air pollution; diet; and hygiene (the result of children being brought up in increasingly germ-free environments).

What are the symptoms?

The symptoms vary, and range from mild to severe. It depends on how much of your colon is affected and the level of inflammation.

Symptoms are often worse first thing in the morning. Symptoms can flare up and then disappear, known as remission, for months or even years. This may be followed by periods when the symptoms are particularly troublesome, known as flare-ups.

Common symptoms include one or more of the following:

- diarrhoea, with or without blood and mucus

- abdominal pain

- a frequent need to go to the toilet

- weight loss

Other symptoms include:

- tiredness (fatigue)

- loss of appetite

- weight loss

- anaemia (shortness of breath, irregular heartbeat, tiredness and pale skin)

- high temperature (fever) of 38°C or above

- dehydration

- a constant desire to empty the bowels

- bloating and gas

- heartburn and reflux

How is ulcerative colitis diagnosed?

The starting point during an initial assessment is for your GP to ask about the pattern of symptoms, your general health and medical history, and whether there is a family history of ulcerative colitis.

An examination will look for signs of inflammation, such as tenderness in the abdomen, and paleness that might be caused by anaemia.

If your GP suspects that the symptoms might point to ulcerative colitis, a referral will be made to a specialist for diagnostic tests.

Tests to diagnose ulcerative colitis may include one or more of the following:

- blood test, to check for inflammation, anaemia and protein levels

- stool sample, which is checked for infection

- X-rays, to help assess the extent of the condition

- sigmoidoscopy, to examine the extent of inflammation in the rectum and lower part of the colon

- colonoscopy, to examine the inside of the entire colon

- how many times you are passing stools

- whether those stools are bloody

- whether you also have more wide-ranging symptoms such as fever, rapid heartbeat and anaemia

- how much control you have over your bladder

- your general well-being

What treatments are available?

There is currently no cure for ulcerative colitis. However, medication can improve symptoms and surgery can also help in many cases.

People with ulcerative colitis have an increased risk of developing bowel cancer and should be monitored regularly, especially if the condition is severe or extensive.

The longer you have ulcerative colitis, the greater the risk is:

- after 10 years the risk of developing bowel cancer is 1 in 50

- after 20 years the risk of developing bowel cancer is 1 in 12

- after 30 years the risk of developing bowel cancer is 1 in 6

People with ulcerative colitis are often unaware that they have bowel cancer as the initial symptoms are similar to ulcerative colitis, such as blood in your poo, diarrhoea and abdominal pain. Because of this, you will probably be advised to have a colonoscopy every few years to check that no cancer has developed.

Alcohol | Aspirin | Body fatness | Dairy | Physical activity | Polyp removal | Red & processed meat | Smoking | Wholegrains

Bowel cancer risk increases significantly when two or more alcoholic drinks are consumed per day.

Please discuss with your GP before taking aspirin.

During childhood and adolescence, be as lean as possible within the normal range of body weight. From age 21, maintain body weight within the normal body mass index (BMI) range.

Throughout adulthood, avoid weight gain and increases in waist circumference.

Include dairy products such as low-fat milk, yoghurt, and cheese, in your daily diet. If you are lactose intolerant or need to avoid dairy for other reasons, speak with your GP or a nutritionist about a daily calcium supplement appropriate for you.

Less than 6% of Australian females aged 19-50 years consume more than 2 serves of dairy or dairy alternatives per day, and only 14% of Australian males in the same age bracket do. Consumption of dairy and dairy alternatives among Australians aged 51-70 is even less, with around two-thirds of both males and females getting less than 1½ serves per day, and one-third of Australians over age 70 consume less than 1 serve of dairy or dairy alternative daily.

Eating too much red meat (e.g. beef, lamb, pork, goat) has been linked with an increased risk of bowel cancer.

Eating processed meats such as bacon, ham, salami and some sausages has been strongly linked with an increased risk of bowel cancer.

Australians aged 19 years and over consume an estimated average of 560 grams of red meat per week.

Smoking 40 cigarettes (two packs) per day increases the risk of bowel cancer by around 40% and nearly doubles the risk of bowel cancer death.